Throughout 2024, international students, along with other immigrants, found themselves on the receiving end of blame for Canada’s economic challenges. Starting with the Jan. 22 announcement of a cap on international student numbers, Canada’s growing political theatre of scapegoating has cast international students as responsible for taking jobs, straining the asylum system, driving up housing costs and increasing pressure on health care.

This kind of blame doesn’t just alienate international students; it demonizes them too. It risks exacerbating everyday discrimination, threats, violence, and even sexual exploitation and human trafficking. In December, University of Regina international students said four men in a car shouted racist insults at them, threatened to shoot them and threw coffee at them.

It also allows the Canadian government to sidestep crucial conversations about the systemic issues at the heart of these longstanding societal challenges. In the public sphere and on social media platforms, threats and vitriol have replaced dialogue.

Read more:

Anti-immigrant politics is fueling hate toward South Asian people in Canada

Among the recent charges leveled against international students is that they are behind a surge in fraudulent asylum claims that is adding to the backlog. Immigration Minister Marc Miller has repeatedly spotlighted international students seeking asylum. In September, he described the rise in student asylum claims as an “alarming trend.” This has in part been used to justify the government’s global ad campaign to discourage asylum seekers.

However, do international students truly make up a significant number of asylum seekers or contribute significantly to the backlog in asylum claims?

What the data shows

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada data reveals that pending asylum claims increased from 71,675 in 2018 to 249,857 in 2024. If international students are a primary factor, data from Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada should reflect this.

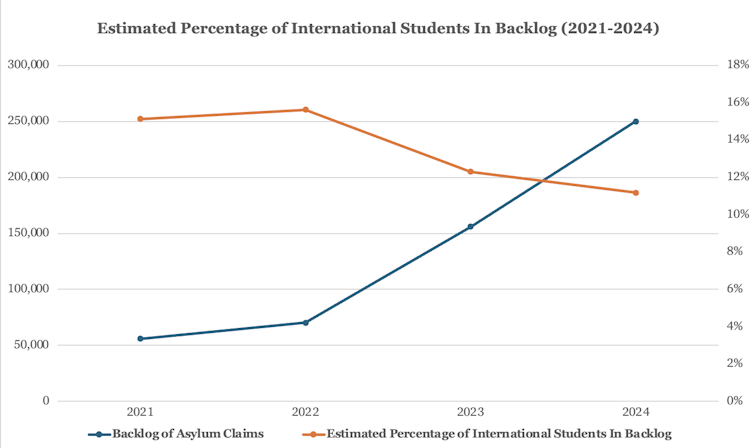

Instead, what the data I have examined shows is that, as an estimated percentage of the backlog, international student asylum claims made up 15 per cent of the backlog in 2021, 16 per cent in 2022, 12 per cent of the backlog in 2023 and only 11 per cent of the backlog in 2024. This shows a decreasing trend over time.

To calculate the estimated percentage, I took the backlog number for each year and divided that number by the sum of the asylum claims made by international students in the three years preceding it, inclusive of that year. The three years is based on the approximate time it has taken for an asylum claim to be processed currently in Canada.

(IRCC/Yvonne Su), Author provided (no reuse)

Put in this way, it can be argued that international students have never been significant contributors to the asylum backlog. Other factors such as increased asylum claims from people fleeing war and conflict and climate-related disasters amid a historic high in global displacement numbers may have had a much larger role to play. However, the increasing demonization of international students has made them among the easiest groups to blame.

A similar pattern plays out when we look at the number of asylum claims from international students as a percentage of all study permit holders. From 2018-2024, there was a total of 33,985 asylum claims from international students. The total number of study permits approved during this period was 1,747,940.

That means only 1.94 per cent of all study permit holders applied for asylum. Given these figures, it is difficult to see how so much can be made about the trend of international students seeking asylum.

Increase in hate-crimes against South Asians

Characterizing international students as bogus asylum seekers abusing the system sends a clear message: international students are the bad guys, they have violated our social contract, and it’s acceptable to treat them as outsiders. This narrative dehumanizes students, reducing them to problems rather than people. And when they are dehumanized and criminalized, it gives people permission to take actions against them.

As a result, reports of racist incidents targeting international students have spiked. Between 2020 and 2023, police in the Waterloo region logged 387 race-based hate crimes, with a significant increase in incidents targeting South Asians as international student numbers surged.

In 2023 alone, South Asians accounted for one in six reported race-based hate crimes, up from one in ten the previous year. Most of these crimes involved threats or graffiti, but 12 per cent escalated to physical assault.

Many international students from India report encountering anti-Indian rhetoric online, including accusations that they take jobs away or harm Canada’s future. These comments exacerbate stress for students already dealing with academic pressures and adjusting to life in Canada.

This rhetoric ignores the real and positive contributions many international students make. It also fuels the discrimination and dangers they can face in Canada.

(Shutterstock)

Misplaced blame

There is a cost to the misplaced blame that needs to be brought to light. When political leaders, media outlets and think tanks frame international students as the main source of societal woes, they miss the opportunity to fix underlying problems.

If health care, housing and education problems are packaged as immigration problems, then politicians can say: “look, we are capping migration, we fixed the problem.”

However, these actions only serve to kick the can further down the road, leaving these problems unaddressed. Furthermore, they also risk creating new problems. Canada has long relied on immigration to increase its population and address labour shortages. When international students are gone, the $37 billion they bring into the economy each year will disappear. When skilled workers from abroad are discouraged from bringing their talents to Canada, who will fill the job vacancies the Canadian economy still needs filled?

Focusing on immigration also means we miss the opportunity as citizens to build any kind of political momentum for policy changes on housing, asylum, health care and education. We need to change the narrative so that politicians and media stop vilifying international students and focus on systemic solutions.

Demonizing international students is not just a rhetorical exercise; it has real, harmful consequences. It licenses discrimination, exploitation and distracts from Canada’s most urgent internal issues. To build a fair and just society, we must reject this scapegoating and demand accountability from the institutions and policies truly at fault.