Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) affects up to half of all women during their lifetime, and one in eight will have surgery to treat it by the age of 85. Yet, despite how common POP is, the public’s awareness and understanding of this condition remains limited.

Most people are unfamiliar with POP until they are personally affected, and even then, are often unaware of the different surgical options available to manage it. Our team of medical professionals and health researchers aims to change this.

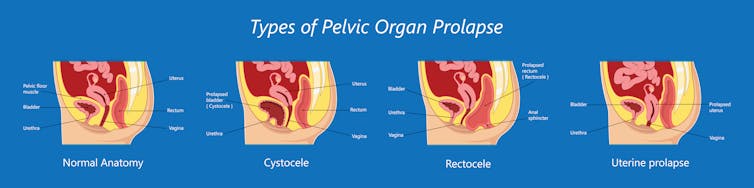

POP occurs when pelvic organs, like the uterus, vagina, bladder or bowel, shift downward and sag into, or even through, the vaginal canal. This condition can lead to a range of physical symptoms, with pelvic pressure, urinary incontinence and a vaginal bulge being some of the most common complaints.

POP can be physically uncomfortable and disruptive to a woman’s quality of life, and the emotional and social impact can be profound. Many affected women report lowered self-esteem, avoidance of intimacy, and heightened anxiety or depression due to the persistent, painful and often stigmatized nature of the condition.

Hysterectomy is the default

For decades, the standard surgical approach for treating POP has generally included a hysterectomy, or removal of the uterus. In many cases, the uterus itself is not part of the prolapse, but removing it allows surgeons to access pelvic ligaments and tissues for securing the vaginal walls. Almost one in three Canadian women aged 60 and older have had their uterus removed to treat a number of gynecologic conditions, including POP.

(Shutterstock)

This surgery is deeply embedded in medical practice with the long-standing belief that removing the uterus is necessary to achieve durable repair of POP, and that the surgery has minimal impact on women’s overall health.

Newer evidence, including recent systematic reviews, questions whether hysterectomy is the only effective approach for treating POP in women. Studies have shown that uterine-preserving procedures carry lower surgical risks compared to hysterectomy surgeries, while providing similar effectiveness in reducing prolapse symptoms.

Adding to this body of evidence, our team of urogynecologists and health researchers developed the Hysterectomy vs. Uterine Preserving Prolapse Surgery (HUPPS) study to generate real-world evidence about outcomes after POP surgery.

Over three years, we enrolled 321 women with POP affecting the top of their vagina who lived in Calgary and surrounding areas of Alberta. Importantly, each woman was free to consider minimally invasive hysterectomy or uterine-preserving POP surgery, based on their own values, preferences and consideration of the evidence. Almost half (47 per cent) chose the uterine-preserving route, which demonstrated substantial interest among Canadian women to keep their uterus when given the option.

However, in many hospitals in Canada, hysterectomy remains the primary approach for surgical treatment of POP, partly due to historical and educational clinical practices.

Surgical outcomes

At one year post-surgery, we found that 17.2 per cent of women who received a hysterectomy surgery experienced recurrence of POP, compared to only 7.5 per cent of women who received a uterine-preserving (UP) surgery. We then statistically accounted for patient differences such as age, body weight and the initial severity of their POP, and found that women who had uterine-preserving surgery indeed experienced approximately half the risk of POP recurrence than the women who had a hysterectomy.

Our data also showed other benefits of uterine-preserving surgery, including shorter operating time, shorter hospital stay, less post-operative opioid pain relief and fewer complications overall.

Why preserve the uterus?

(Shutterstock)

Emerging research suggests there can be long-term effects of hysterectomy. For example, hysterectomy may be associated with elevated risk of chronic health issues such as cardiovascular disease and neurological disorders. These risks are higher for people who undergo hysterectomy at younger ages.

However, there can be instances where patients may want to consider hysterectomy as part of their POP repair. These include a history of repeated abnormal pap smears signalling a higher risk of developing cervical cancer in the future, or in cases where it is strongly recommended to them by a surgeon, such as when precancerous cells have been determined by a biopsy of the uterus.

For people without these conditions, there is no medical need to remove the uterus.

However, the historical hysterectomy-based approach to POP assumes that all women want the same approach to their POP treatment. However, during the past five years, our team has noticed growing inquiries from patients around keeping their uterus, and questions about the risks and benefits of a hysterectomy.

Some women want to avoid hysterectomy due to personal or cultural beliefs about removing their uterus, while others are concerned about the potential long-term effects on their health. The International Urogynecological Association has a helpful pamphlet with more information on this topic.

The importance of patient-centred care

Our research findings, combined with growing evidence on surgical treatment of POP, encourage an essential shift in the field of gynecological surgery towards an approach that offers all women a greater sense of autonomy.

The HUPPS study demonstrates that when people are presented with evidence-based information on the risks and benefits, they can choose the option that aligns with their personal values and long-term health goals and still achieve a good surgical outcome.

For women in Canada who are affected by POP, this means ensuring that two options are offered and accessible to them: both hysterectomy and uterine-preserving surgeries. If we can achieve a permanent shift in the medical landscape towards more informed, personalized and patient-centred care, it will change women’s lives for the better.