The scene at the end of the 19th century in what was known as Indian Territory — at one point encompassing most of the present-day United States west of the Mississippi River —

would seem familiar to anyone following the news about the crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Illegal immigrants streamed in, and some leaders had seen enough.

Nationalists among the Chickasaw Nation called for a mass deportation of white U.S. citizens. One Chickasaw leader, Judge Overton Love, wrote that undocumented whites should be “placed under arrest immediately and hustled out of the country with strict orders not to return.”

Muscogee leaders reported intruders to the federal government. U.S. marshals escorted white migrants to Arkansas and hit them with a US$1,000 fine. But they returned, again and again.

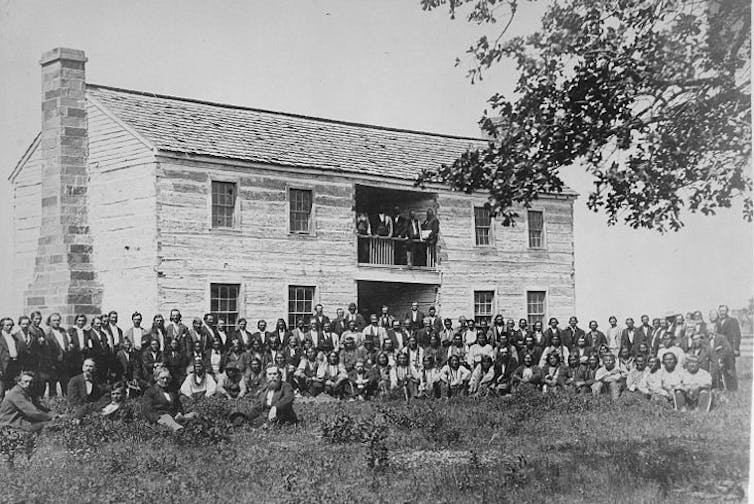

(National Archives)

Illegal invasion

Among those intruders was my great-great-grandfather, Bill Hogan. Bill was an illiterate white sharecropper in Yell County, Ark. He migrated with his family to the Muskogee Nation sometime around 1900, probably following a new railroad line.

(Russell Cobb), Author provided (no reuse)

Predatory landowners in the South made life difficult for poor white people like Bill, and nearly impossible for Black people. But freed slaves founded prosperous all-Black towns like Boley, just down the road from Bill’s homestead near Eufaula.

The illegal invasion of sovereign nations by white American citizens occurred all over the West, from Texas to South Dakota. Mexican authorities even worried about a flood of U.S. citizens re-introducing slavery into the republic, and banned U.S. immigration in 1830.

This did nothing to stop the flood of Americans from claiming land. A treaty prohibiting U.S. citizens from settling in the Great Sioux Reservation was blatantly violated by hundreds of gold prospectors in the 1870s.

When Oklahoma became a state in 1907, the U.S. effectively closed a chapter on 100 years of invasions and illegal land seizures in the western United States. A century later, conservative leaders have been claiming the U.S. is now the nation under threat of invasion, conveniently ignoring this long and complicated history.

White supremacy doctrine

It is common to hear that the U.S. immigration system is broken, but it was never fixed. Migration to and from sovereign Indigenous nations, Mexico and even Canada has always been subject to waves of xenophobia and fear. A political wind of change can turn intruders into pioneers, as happened on a massive scale among the Five Tribes in Indian Territory.

Bill Hogan may have been in the Muscogee Nation illegally, but he was accepted by his Muscogee neighbours by 1901. The Indigenous-published Indian Journal reported on his travels around Indian Territory in local news, and his son, Jordan, started to achieve some prosperity. The Hogans intermarried and my grandmother lived with a Choctaw man. She is buried next to a Muscogee family in the Checotah cemetery.

Editors and politicians back in the States noticed this unique mixture of native governance, poor white subsistence farming and Black town-building. They were not impressed. It was anathema to white “civilization.” The tri-racial experiment of Indian Territory was crushed by a doctrine of white supremacy established in new state laws.

Unlike today’s unauthorized immigrants, white intruders had political power and influence to change the law. The Indian Appropriations Act of 1902 made it illegal “to remove or deport any person from the Indian Territory who is in lawful possession of any lots or parcels of land in any town or city…which has been designated as a townsite.”

Just like that, ownership of land now protected white intruders like my ancestor if they owned land. Imagine the shoe on the other foot today: U.S. Congress passes a law protecting unauthorized immigrants from deportation because they own some real estate in an Oklahoma suburb.

(Library of Congress/Russell Lee)

There is a crucial difference between Bill Hogan crossing into Indian Territory and the current wave of migrants arriving in the United States. These new “intruders” do not want land.

The few stories of Latin American migrants seeking to claim land through squatters’ rights have little legal credibility. Unlike the settlers that pushed the Cherokees, Chickasaws and others off their allotted lands in Oklahoma, the new migrants are not really settlers at all. They are labourers.

The story of Leo Bennett

The U.S. Marshall tasked with enforcing migration laws in Indian Territory, Leo Bennett, found himself in the crosshairs of some who wanted mass deportation and others who wanted the termination of Indigenous governance.

Bennett was married to a Cherokee woman and empathized with Indigenous leaders who resented the intruders. Bennett promised to deport known law-breakers, but he resisted the calls to ban all migrants.

Chickasaw leaders were rightly afraid of people like the notorious outlaw Dan “Dynamite Dick” Clifton. But Dynamite Dick did not represent the majority, and so Bennett would not enforce mass deportation. Most Indigenous leaders agreed with him.

Some of the whites milked cows, ran hotels and serviced the trains. If all whites were deported, they would only return again, hungrier and more determined. Bennett wrote in a local paper that “equity as well as law must be so administered that justice shall be tempered with mercy.” He wanted “fairness toward all concerned,” but fairness, then as now, was easily reframed as weakness.

Those ideals — equity, mercy and fairness — require a historical reckoning over how the United States acquired its contemporary boundaries in the first place. Those ideals also require compassion for newcomers, whether they’re white men from Arkansas in 1901 or a Haitian family in Springfield, Ohio in 2024.